- Kazys Seselgis:

INTRODUCTION

-

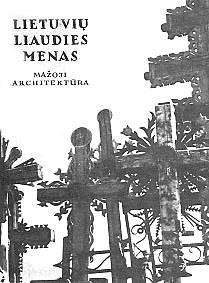

- For many centuries monuments, such

as pillar-type crosses, roofed pillar-type crosses, ordinary

crosses and miniature chapels, played a significant part in

Lithuanian folk architecture. While farm buildings were built to

satisfy everyday needs, such as for example, storing goods,

monuments were

not

related to any material necessities and served exclusively the

spiritual needs of the people. Monuments used to be erected to

commemorate significant events and dates in the lives of families,

village communities and also in the political, social and cultural

life of the nation. There are monuments dedicated to honor the

fallen in the uprising of 1863, to commemorate the

proclamation of the independent Republic of Lithuania, and the

Year of Vytautas the Great, and also monuments marking significant

events in church life. But such monuments are not very numerous.

Most of the crosses were erected by individual families over the

graves of their relatives, at the places of accidents, on the

occasion of great blessings or misfortunes, at the birth of the

long-awaited heir, to mark good fortune on the farm or in personal

life, as the fulfillment

not

related to any material necessities and served exclusively the

spiritual needs of the people. Monuments used to be erected to

commemorate significant events and dates in the lives of families,

village communities and also in the political, social and cultural

life of the nation. There are monuments dedicated to honor the

fallen in the uprising of 1863, to commemorate the

proclamation of the independent Republic of Lithuania, and the

Year of Vytautas the Great, and also monuments marking significant

events in church life. But such monuments are not very numerous.

Most of the crosses were erected by individual families over the

graves of their relatives, at the places of accidents, on the

occasion of great blessings or misfortunes, at the birth of the

long-awaited heir, to mark good fortune on the farm or in personal

life, as the fulfillment

of a promise amongst other reasons.

- Once erected, a cross, a pillar-type

cross or a miniature chapel was regarded as a sacred thing: nobody

dared to inflict any damage to it or show disrespect by indiscreet

behavior near it. During the summer festivals (e. g. Whitsunday)

such monuments used to be decorated with wreaths, cemeteries and

individual monuments were visited by processions in

which the entire village population usually took part. The area

around them was constantly taken care of by planting flowers and

shrubs, by weeding the paths and by sprinkling them

with sand. This was supposed to strengthen the ties between the

living and the dead, a link

with the past, and was one of the ways of maintaining a balance

between the material world

and man's spiritual life. Some monuments, especially those in

Dzukija, acquired the fame

of possessing magic powers, and then people's contacts with them

took on quite a different

aspect. For example, as late as the seventies of the present

century brides still continued to

gird the stems of crosses with towels and aprons in the Zervynos

village, Varena District,

entreating God to bless them with an heir. The traditions of

deifying monuments and attributing great powers to them are very

old, for they seem to have come down to us from the

pagan times.

- Monuments used to be erected in

farmsteads, by the wayside, at crossroads, on river banks, in

cemeteries, churchyards, streets and squares of towns and villages

and other places visible from afar, related to some commemorable

event. Their distribution corresponded with the concentration of

farm houses: the largest clusters of monuments were to be found in

the old type villages and village cemeteries, while in the areas

where farmsteads were dispersed at considerable distances,

monuments were much sparser.

- Crosses, pillar-type crosses and

miniature chapels gave the village carpenters, sculptors and wood

carvers a better chance to display their capabilities than any

other objects of folk architecture. Here they could realize the

old creative traditions handed down to them by their predecessors,

and thus produce works of high artistic standards. In these

structures folk masters strove to express the joys and misfortunes

that befell the village people of their time, to embellish and

enoble their everyday life and surroundings. The craftsman always

worked in close collaboration with his patron, who was also a

simple farmer. The patron's wish to have one of these monuments

was usually the decisive factor which determined the content of

the monument and its form (a cross, a pillar-type cross, a roofed

pillar-type cross or a miniature chapel). The distribution of

these monuments in Lithuania depended a great deal upon the

patrons. But the master himself was usually free to carry out the

commission as he thought best and, in doing this, he relied both

on the traditions of his predecessors and his own artistic

creativity. Therefore the master alone, as a rule, was honored as

the one who gave expression to people's spiritual values. It would

be rather difficult to determine the exact part which the master

and the patron played in the development of memorial architecture

and its ethnographic features, but we should not underestimate the

part played by the latter. Whatever the world outlook of the

simple people of the distant past, whatever their attitude and

reaction to the relationship of the material and metaphysical

elements, whatever the means used to realize people's spiritual

aspirations, they all had a share in the content and forms of

memorial architecture.

- We can imagine the following

sequence in the creation of a memorial monument: the patron makes

his wishes plain to the craftsman. In giving his instructions, he

proceeds from his own understanding of the world and the artistic

conventions used throughout a long period of time to express

spiritual values. In addition to the factors indicated above, the

master is influenced also by the landscape and surroundings of the

future monument (a cemetery, a farmstead, a street, a roadside,

and so on), by the prevalent architectural styles, and the

compositional innovations discovered and utilized by other

masters. For

example, Baroque sculpture and ornamentation had a great influence

on the well-known master of crosses, Vincas Svirskis (around the

turn of the 20th century), while his own original compositions

served as models for other masters who worked in the same district

(e. g. Samuolis). But on the other hand, his monuments would not

have been admired, loved and honored so much by the simple folk if

he had used architectural forms outside the general artistic norms

which formed part of their everyday life. Inattention to the

values of national spiritual culture and folklore, disregard of

the accepted interpretation of the past and disrespect to the

native language are incompatible with any measure of sincerity

in the small-scale forms of architecture or the continuation and

use of centuries-old artistic traditions. This truth was only too

manifestly confirmed during, the first post-war years when,

through administrative measures, attempts were made to channel the

natural development of folk memorial architecture into a new

direction.

- Memorial monuments were built of

stone, bricks, iron and, beginning with the 20's of the present

century, concrete. But the greatest number of them was made of

wood. All of them were topped with iron heads. Monuments, which

were made exclusively of iron or stone were rather rare; elaborate

iron crosses used to be fixed in natural field boulders specially

selected for the purpose or roughhewn stems of stone. As bricks,

stone and concrete were not easy to model, monuments made of these

materials were rather modest and laconic, conspicuous among the

trees or against the sky by the simple cross-like shape alone.

Wood and iron provided better possibilities for the masters to

demonstrate their talents, therefore wooden and iron monuments

displayed the greatest variety of forms. There were several kinds

of constructions typical of wooden monuments: a stem with a roof

(roofed pillar-type monuments), a stem with one or several

cross-pieces (crosses), a box with one of its sides open, topped

with a saddle, hipped, broach or, more rarely, conical broach roof

(miniature chapels). Alongside, there were monuments of mixed

construction: a combination of a tall vertical stem and a

miniature chapel (pillar-type crosses) or a cross and a miniature

chapel. According to the type of the construction it is customary

to distinguish five typological groups of wooden monuments: roofed

pillar-type crosses, pillar-type crosses, ordinary crosses,

miniature chapels and carved memorial boards - krikstai.

Each typological group had an infinite variety of forms - it has

been impossible to discover two absolutely identical monuments

even if they were created by one and the same master (here again

we can recall, for example, the works by Vincas Svirskis).

Typological variation is one of the outstanding features of

Lithuanian folk architecture.

- To satisfy the simple people's

insatiable desire for beauty, folk monuments used to be profusely

decorated with openwork, contour and relief carvings or turned

work ornaments. True, there were crosses, which had no decorative

elements whatever, except for the slight ornamentation of the

stem, but there were many more in which lavish decorations

smothered even the very sign of the cross. Wooden miniature

chapels were decorated, as a rule, quite moderately, pillar-type

and roofed crosses, on the contrary, used to be decorated rather

heavily. The decorative elements on the krikstai, which

used to be erected on graves in the coastal districts (the

Klaipeda region), made an inseparable part of their construction:

the board, which bore the inscription of the deceased person's

name, was first painted, then geometrical ornaments or stylized

plants and animals were cut out along the

edge. The motifs of decorative elements fall into three groups:

(1) geometrical abstract ornaments, (2) stylized birds and animals

(grass-snakes and, more rarely, horses), plants (daisies, potted

flowers, leaves of various shapes, blossoms and buds), heavenly

bodies (suns, moons, stars), and (3) Christian iconographic

symbols and ecclesiastical attributes (liturgical vessels,

monstrance’s, spears, ladders, etc.). The most popular of them

were open-work geometrical ornaments, then followed the stylized

plant ornaments and the sun and moon motifs, which were usually

masterfully inserted into the iron heads of the monuments.

- Through the arrangement of

decorative elements the artist strove to concentrate the viewer's

attention on the most important part of the monument. Thus, for

example, the most heavily decorated part of a cross was usually

the point of intersection of the stem and the cross-piece, for

this was the place where a model of the crucified Christ or a

little chapel with the figures of saints within used to be

attached. On a miniature chapel decorations were usually

concentrated around the edges of the open side, showing the

statuettes within.

- The statuettes on the monument were

very important, for they expressed its main idea. The chapel, for

example, was very often regarded only as a temporary home for the

patron saints, which gave them shelter from rain, snow or the

wind. In this respect, miniature chapels occupied a unique place

amongst small-scale folk architecture. To a farmer only the

statues within the chapel seemed to be sacred, so that in troubled

times he would save only the saints by bringing them home and

leave the chapel to its own fate. It could be the reason why

outwardly miniature chapels reminded so much of barns, porches or

miniature shrines, i. e. constructions designed to give temporary

or permanent shelter to people. Thus, the miniature chapel was, in

fact, just a home for the deified statues. The place for the

miniature chapel to be installed in was selected and the

statuettes were arranged inside so that

they should not resemble a display of stationary exhibits but

remind of living beings looking through the window of the chapel

at the everyday life of the farmer's family, at the carts passing

by on the road and the corn fields stretching far and wide. The

windows of the chapel and the glass door were usually adorned with

embroidered or lace curtains and paper flowers. The idea was to

express love and respect for the humanized gods, and create as

much comfort for them as possible. As a rule, miniature chapels

contained more than one statue, and they used to be arranged in

scenes from Christ's and the saints'

lives. Statuettes are important on pillar-type and roofed

pillar-type crosses as well, but on these monuments their

emotional impact is usually suppressed by numerous other

decorative elements. Here the statuettes lose much of their

independent function as the central pieces of the monument and

serve mostly as mere decorations.

- The semantic and artistic value of

the statuettes attached to crosses is even less. The greater

number of these monuments have a model of the crucified Christ

attached at the intersection of the stem and the crosspiece. Its

artistic value depended mostly on the master's ability to handle

the same canonized form in any original way.

- In the second half of the 19th

century, when iron could be afforded by middle-class farmers, iron

heads, most often referred to as little suns, became an

inalienable part of every miniature chapel, pillar-type cross and

roofed pillar-type cross. Very soon iron head forgers managed to

attain really high artistic standards. The unity of the wooden and

iron parts of the monument was usually ensured by choosing the

right scale and the proper proportions in the arrangement of the

stylized ornamental motifs.

- Small-scale folk monuments usually

harmonized quite well with the farm buildings, which was due both

to their wellchosen dimensions and similar decorative elements. In

ornamentation and composition there was little difference between

the monuments and the dwelling houses. We find the same kind of

decorations in the trimmings of gables, windows and porches, as

well as on household utensils, such as laundry beetles, spinning

wheels, distaffs, and furniture - towel hangers, cupboards, dowry

chests, chairs, benches, etc.

The unity of the artistic forms used in the exterior and the

interior of farmhouses and farmyards was ensured by the continuity

of the efforts of many generations. It has become a tradition in

Lithuanian folk architecture, which is the best reflection of the

spiritual needs of its creators.

- This publication in the series of Lithuanian

Folk Art is devoted to miniature chapels and crosses. It

should be viewed as the second volume of Small-scale

Architecture, published in 1970 and devoted to pillar-type and

roofed pillar-type crosses.

- Miniature chapels used to be built

of bricks, field boulders or wood. The forms of those built of

brick are rather simple, without any traces of having been

influenced by the prevalent architectural styles. Most of them are

rectangular or, more rarely, round. On one or several sides,

depending on the visibility of the chapel, there are niches for

statuettes.

Every miniature chapel is topped with an iron head, which may be

quite simple or, on the contrary, rather elaborate. Brick chapels

are usually plastered; when a miniature chapel is built of

boulders, the binding seams are nicely molded. Brick and stone

chapels, just like other monuments, used to be erected at

crossroads, by the wayside or, more rarely, in farmyards or over

graves. Very often they were built to adorn the entrance to

churchyards and cemeteries. Commissions for brick chapels used to

come from village communities, parishes or the local rich. Simple

peasants favored wood, which was a cheaper and more traditional

building material. Although brick chapels are to be found all over

Lithuania,

their number is much less than that of the wooden monuments.

- Wooden miniature chapels were

usually built on the ground or fixed up in the trees or onto

walls. Those on the ground were either rectangular, round or

cross-like, with columns or without at the facade, covered with

roofs of different configuration (saddle, hipped, broach or

conical broach roofs). They also differed from each other in the

degree of openness (open at the facade, on three or all the four

sides), in the number of stores (one- or two-storied

constructions) and the foundation (made of unbound boulders, brick

or stone masonry, or just a wood log frame). Outwardly, wooden

chapels were rather laconic,

with sparing decorative elements, the ornamentation of the iron

heads being the only focal point. This was quite in keeping with

the general tendency, observed in the folk architecture of the

Lowlands where wooden miniature chapels were the most frequent.

This tendency was to seek beauty not so much through an abundance

of decorative elements, which was so characteristic of folk

architecture in the Highlands, as through the overall harmony of

their constituent parts, their admirable proportions and their

unity with the natural environment. In this architectural context,

the laconic forms of the wooden chapels blended very well with the

whole architecture of farmsteads.

- Chapels, hoisted in trees, developed

in a different direction: as they occurred in every ethnic region

of Lithuania, their architectural patterns matched the local

architectural traditions. Accordingly, their forms were more

varied than those of the chapels built on the ground: they ranged

from simple box-like carcasses with saddle roofs to very posh

structures immitating Baroque or neo-Gothic constructions.

- Wooden crosses, with one or, more

rarely, with two or three cross-pieces, were the most frequent

forms of memorial architecture in the Lithuanian countryside. They

were constructed in different compositional and decorative

patterns, which included sculpture and various interpretations of

chapel and altar motifs. The latter were used as decorative

elements at the intersection of the stem and the crosspiece and

served as repositories for statuettes. There were several

variations of decorative elements used on crosses: carvings on the

stem and the cross-piece, open-work ornaments fixed on the stem,

open-work ornamentation of the intersection of the stem and the

cross-piece, decorative chapels or altars attached to the main

construction, iconographic symbols placed on the sides. Quite

frequently several ways of ornamentation were used together on one

and the same monument.

- Every ethnic region had its own

traditions in the use of decorative and compositional patterns.

For example, in Eastern Highlands the stem and the cross-piece

were very frequently adorned with open-work cuttings. In Dzukija,

crosspieces were often supported by spears, which minimized the

visual significance of the sign of the cross in the overall

composition of the monument. In the Lowlands crosses were less

numerous and decorative elements were used on them rather

sparingly.

- To a large extent, the style of the

crosses in every ethnic region was determined by individual

masters of outstanding talent who worked there. At the turn of the

20th century one of such masters was Vincas Svirskis, who lived

and worked in the districts of Kedainiai and Panevezys. Every

single cross made by him was a prominent specimen among the

traditional crosses turned out by the other, less gifted, masters

of these districts. Although the influence of church Baroque

sculpture on Svirskis' crosses was unmistakable, they cannot be

said to have been just mere immitations. On the contrary, they

were creative interpretations of the decorous Baroque forms

blended with the compositional conventions of Lithuanian folk

sculpture. Discarding the usual technique of mounting a cross from

separate architectural parts and decorative elements, Svirskis

took to carving crosses from a solid piece of a tree trunk, most

often an oak. He also attached a good deal of importance to the

place where the monument was to be erected and its visibility. He

sought that his monuments should be equally impressive when viewed

from every point of observation.

If the monument was well visible on all the four sides, the master

took care to decorate evenly all the four facades; if it was

visible on two sides, two facades were decorated; if it was

visible only from the front, it was the front that carried all the

decorations. In this respect Svirskis broke away from the

prevailing Highlands' tradition of erecting crosses where

they could be viewed only from the front and, accordingly, of

concentrating all the attention

on their facades. He preferred to adapt the composition of his

crosses to where they were

going to stand, and that was his new original method, his

trademark so to say. This folk

artist built about 200 crosses, each one of them peculiar for its

shape, sculptures, bas-reliefs and arrangement.

- In Svirkis' monuments the cross, as

the main iconographic symbol of Christianity, which had always

been the focus point in all the traditional cross compositions,

gave way to masterly highreliefs depicting scenes from the life of

Christ and the saints, and to the sculptures of popular saints,

such as St John the Baptist, St Isidore, St Florian and others.

The outward appearance of his statues, their robes and typical

postures resembled simple farmers in the Lithuanian countryside.

This made them very dear to the hearts of the common people.

The monumental quality of Svirskis' crosses was achieved mostly

through the expressive figures of the saints and their elaborate

groupings.

- The outstanding talent of this folk

artist and his original artistic conceptions could not escape the

attention of his contemporaries. But his followers, alas, failed

to achieve the artistic heights of their teacher. The original

monumental style, created by Vincas Svirskis, did not receive

subsequently any appreciable development, most probably because it

differed too much from the standard forms of folk architecture and

represented a leap in the Lithuanian creative traditions rather

than their gradual development.

- Wood is not a very durable material;

it decays rather quickly, especially when in contact with the

soil. In several decades after the erection wooden crosses had to

be repaired: their stem had to be shortened by sawing off the

decayed lower part. Thus, the proportions of such a cross-changed.

The greater number of the 19th century crosses, shown in the

photographs of the present publication, have already lost their

original height.

- Folk monuments of the kind

represented in this publication also served the purposes of visual

information about the local people's spiritual culture, their

aesthetic views and understanding of beauty. Rather a short time

ago miniature chapels, crosses, pillar-type and roofed pillar-type

crosses constituted an inseparable part of Lithuanian

landscape.

Not only did they bear witness to the high standards of folk

artistic traditions and the talent of individual masters, but they

also shaped and beautified the rural scenes around them.

- A passer-by could not help noticing

the aesthetic impact of the monuments on their surroundings simply

because they occurred in great numbers, and the variety of themes,

depicted in them, their artistic forms and arrangement were just

inexhaustible.

- In 1938, Prof. Ignas Koncius, who

was an enthusiastic recorder of folk small-scale architecture,

drew up a list of such monuments which were found at the time by

the wayside in the Lowlands. According to this list, there were

3100 monuments west of the

Jurbarkas-Erzvilkas-Uzventis-Tryskiai-Lauzuva line (the Klaipeda

region excluded). That means that there were 1.3 miniature chapels

or some other kind of monuments to every single kilometer. If we

add to this number the monuments, which stood at some distance

from the roads, in farmsteads and village cemeteries, their

general number would amount to 6

or 7 thousand, or 0.4 item to every square kilometer. These

impressive numbers could not help leaping into the eye and could

not fail to produce a considerable effect on the rural scene.

- Only a miserable fraction of this

priceless wealth of folk architecture has survived to the present

day. In the ethnic area explored by prof. Ignas Koncius mere

0.35-0.5 per cent of the former monuments have been preserved. A

little more monuments have remained in farmsteads, churchyards and

cemeteries, for there they have been looked after by their owners

and patrons.

- There were two causes responsible

for this drastic decrease in the number of folk monuments: natural

causes (wood is a fairly short-lived building material) and, which

is much more important, the ideological policy in Lithuania after

World War II. A large number of memorial items were purposefully

destroyed even as late as the 70's. The construction of new

monuments was officially frowned upon, so that in order to avoid

trouble, people simply stopped building them. Whatever new

monuments appeared in more remote places, at some distance from

big roads, they were rather modest, and even poor, from the

artistic point of view. In an attempt to save the old wayside

crosses and chapels, people used to

transfer them to farmsteads, but this was done only in case their

patrons had been individual farmers and they continued to reside

in their old homes. Crosses and chapels erected at the sponsorship

of village communities were usually, left to their own fate.

- Before the war, decayed wooden

monuments were usually repaired or replaced by new ones so that

their total number remained approximately the same all over

Lithuania. When building new crosses, chapels and other monuments,

folk masters strove to keep to the traditional artistic forms, for

the main principle in folk art were the continuity of its forms,

which guaranteed the endurance in the general appearance of the

architectural monuments and the rural scene. After the war this

natural continuity was broken and the country scene lost one of

its most important and characteristic anthropogenetic elements.

The builders of the new rural settlements and recreational

complexes lost the natural source which enabled them to achieve

and perpetuate in the new constructions the traditional folk art

forms which blended so well with their natural surroundings. Now

we can judge about what we used to

have and what we have lost only from the scanty remains, but

mostly we judge about that from the photographs of memorial

architectural objects amasses in the stocks of our museums. We

have inherited the most valuable collections of photographs of the

pre-war crosses and chapels from the ethnographer Balys Buracas,

prof. Ignas Koncius, and the artist Adomas Varnas. After World War

II folk architecture has mostly been investigated by the

Ethnographic department of the Historical Institute of the Academy

of Sciences of the Lithuanian SSR. Every year Lithuanian museums

(Ciurlionis Art Museum in Kaunas; Lithuanian State Art Museum;

Lithuanian Historical and Ethnographic Museum) do a lot of field

work registering and producing pictorial evidence of the objects

of folk memorial architecture. A good deal is done in this respetc

by professional photographers and laymen.

- The material contained in this book

is arranged according to the typological peculiarities of the

monuments. The indication of the location of the object, which is

represented in the photograph, enables the reader to form some

idea about the regional distribution of certain types of

monuments.

- The preparation of this art book was

started in 1968 by the late prof. Klemensas Cerbi lenas, an

indefatigable collector of the evidence of Lithuanian folk

architecture in museun and private collections, by Decent Feliksas

Bielinskis, an invaluable consultant on the selection of material

for this publication, and by Kazys Seselgis. It is a shame the

book we not published then. Now when the primitive attitude to the

content and forms of folk art and architecture has changed, the

publication of this book has become possible at last. Alas, the

final selection and arrangement of the material has inevitably

been done by the only survivor of the original group of three.

- The book is meant for artists,

architects, art critics and the public at large, interestec in the

heritage of Lithuanian folk culture and its development. It is our

hope that it will contribute to the proper understanding of

the enormous wealth created by the talentec hands of simple

village people, and will engender a wish to seek ways for its

better preservation so that it might serve as an inexhaustible

source in the creative efforts to perpetuate and enrich Lithuanian

national culture.